Perhaps one of the most well-known numeric sequences, the Fibonacci sequence sees each number as the sum of the two preceding numbers. Starting with \(0\) and \(1\), we can find the next element by doing \(0 + 1 = 1\), then \(1 + 1 = 2\) and so on. The first 10 Fibonacci numbers are \(0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34\). The Fibonacci sequence can be defined by the recurrence relation:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathrm{F_1} &= 0 , \mathrm{F_2} = 1 \newline \mathrm{F_n} &= \mathrm{F_{n-1}} + \mathrm{F_{n-2}} \end{aligned} $$

On an unrelated note, I started learning the Rust programming language last year. While reading about the Fibonacci numbers, I started thinking to myself, "Hey, I should write a Rust program to generate these!" But that begs the question, how fast can I calculate these Fibonacci numbers? Can Rust provide me any unique benefits towards this goal? In this exploration, I try to calculate the largest Fibonacci number possible in under 1 second, in Rust.

The Naïve Approach

The obvious way to calculate Fibonacci numbers in Rust would be to directly translate the recurrence relation above--in other words, the recursive approach. The code for this is pretty simple actually:

pub fn fib_recursive(n: usize) -> u128 {

match n {

0 => 0,

1 => 1,

_ => fib_recursive(n-1) + fib_recursive(n-2),

}

}

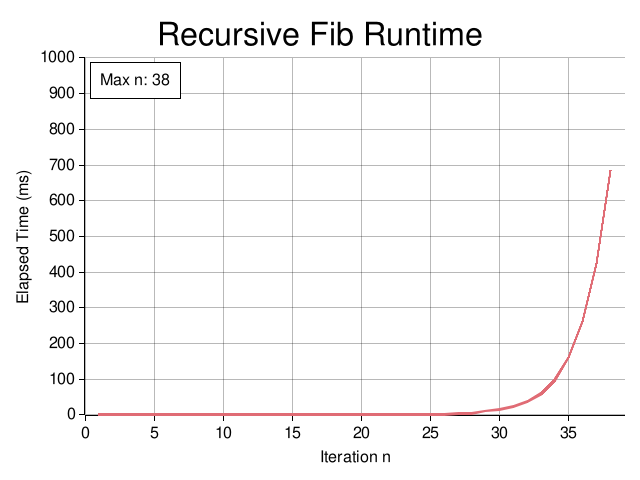

Simple, but not really practical. This algorithm has exponential time complexity, let's call it \(O(2^n)\). The runtime graph below is pretty pitiful, as we can only calculate the 38th Fibonacci number this way. I could do that with a pen, paper, and a free afternoon!

Sliding Window

This next algorithm is a substantial improvement over the last and one of the most commonly used Fibonacci algorithms.

pub fn fib_slidingwin(n: usize) -> u128 {

let (mut a, mut b) = (0, 1);

for _ in 0..n {

let t = a + &b;

(a, b) = (b, t);

}

a

}

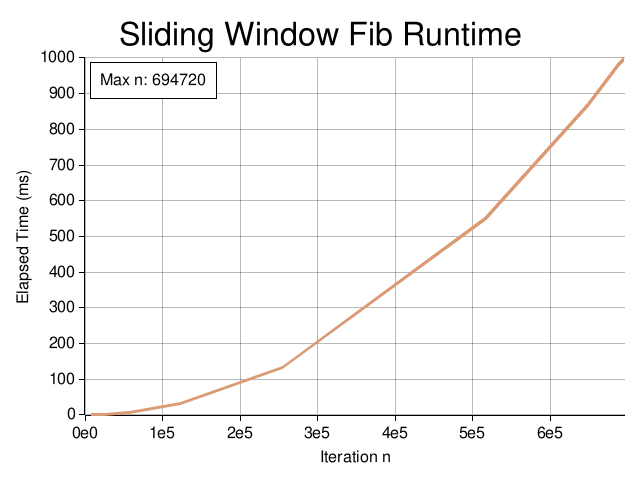

This algorithm runs in linear time, \(O(n)\). We quickly run into an issue though; the maximum

value a u128 integer type can hold is \(2^{128} - 1 \approx 3.40 \times 10^{38}\). The largest

Fibonacci number within this bound is \(\mathrm{F_{186}} \approx 3.33 \times 10^{38}\), so we won't be

able to calculate any terms after 186. We must use a type that can handle arbitrarily large integers.

Big Integers

I use the num_bigint crate

which gives us the type BigUint, a vector of digits. The capacity of this type is still limited

by the underlying allocator and operating system, but it should be enough to store any

Fibonacci number we need.

Implementing this with the example above we get:

pub fn fib_slidingwin(n: usize) -> BigUint {

let (mut a, mut b) = (BigUint::zero(), BigUint::one());

for _ in 0..n {

let t = a + &b;

(a, b) = (b, t);

}

a

}

Let's see what the runtime graph looks like:

Matrix Multiplication

This next algorithm makes use of a lesser-known matrix identity for the Fibonacci numbers. Start with the observation that:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \newline 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1 \newline 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 2 \newline 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

$$ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \newline 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 2 \newline 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 3 \newline 2 \end{bmatrix} \newline \dots $$

In general, the square matrix \(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \newline 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \) sends \(\begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{F_{n}} \newline \mathrm{F_{n-1}} \end{bmatrix}\) to the "next" vector \(\begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{F_{n+1}} \newline \mathrm{F_{n}} \end{bmatrix}\):

$$ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \newline 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{F_{n}} \newline \mathrm{F_{n-1}} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{F_{n}} + \mathrm{F_{n-1}} \newline \mathrm{F_{n}} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{F_{n+1}} \newline \mathrm{F_{n}} \end{bmatrix} $$

Using similar logic and the magic of induction, one can show that the square matrix "generates" Fibonacci numbers:

$$ \boxed{ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \newline 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} ^{n} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{F_{n+1}} & \mathrm{F_{n}} \newline \mathrm{F_{n}} & \mathrm{F_{n-1}} \end{bmatrix} } $$

This is the formula I used for my Fibonacci algorithm! If we can multiply \(n\) matrices, we can get the \(n+1\) Fibonacci number. In theory this has \(O(n)\) runtime complexity since we perform an \(O(1)\) matrix multiplication $n$ times, but we can do better.

Binary Exponentiation

Binary exponentiation or exponentiating by squaring is a method to calculate integer powers of a number in \(\lceil \log_2 n \rceil\) multiplications instead of \(n\). We start by writing the exponent in binary as such:

$$ \begin{aligned} 3^{11} & = 3^{1011_2} \newline & = 3^8 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 3^1 \newline & = 6561 \cdot 9 \cdot 3 \newline & = 177147 \end{aligned} $$

The key realization here is that we can get \(3^2\) by squaring \(3^1\) and \(3^8\) by squaring \(3^2\) twice. In this way, we can "build up" to our answer by squaring each term for the next power of two:

$$ x^n = \begin{cases} (x^\frac{n}{2})^2 & \text{if } x \text{ is even} \newline x \cdot (x^\frac{n-1}{2})^2 & \text{if } x \text{ is odd} \end{cases} $$

We can recurse on \(x^\frac{n}{2}\) or \(x^\frac{n-1}{2}\) until we get to \(n=1\), at which point we stop. So the complexity is \(O(\log n)\): we compute \(\log n\) powers of \(x\) and do at most \(\log n\) multiplications.

I use an iterative version of this algorithm with the above Fibonacci matrix identity to compute Fibonacci numbers in \(O(\log n)\) time. Here's how it's done:

/// Calculates A^n where A is a 2x2 matrix and n >= 0

fn matrix_pow(mut a: [[BigUint; 2]; 2], mut n: usize) -> [[BigUint; 2]; 2] {

let mut res = [

[BigUint::one(), BigUint::zero()],

[BigUint::zero(), BigUint::one()],

];

while n > 0 {

if (n & 1) == 1 {

res = matrix_mult(&res, &a);

}

a = matrix_mult(&a, &a);

n >>= 1;

}

res

}

/// Entry point

pub fn fib_matrixmult(n: usize) -> BigUint {

let f = [

[BigUint::one(), BigUint::one()],

[BigUint::one(), BigUint::zero()],

];

let fib_n = matrix_pow(f, n - 1);

fib_n[0][0].clone()

}

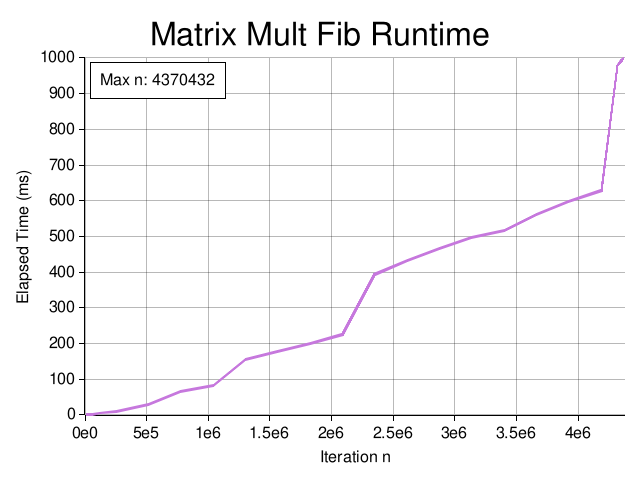

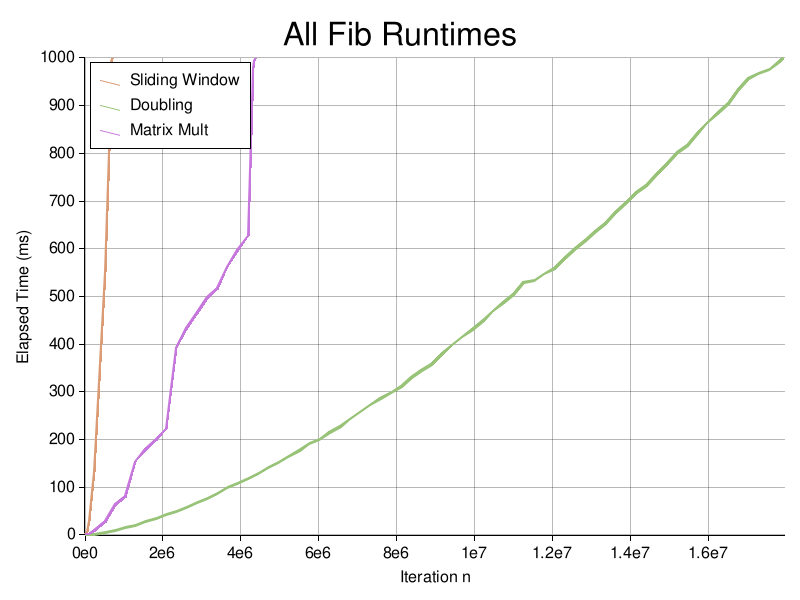

Here matrix_mult is a function that multiplies 2x2 matrices. Looking at the graph,

we achieve a significant improvement over the sliding window method, with a maximum

iteration of \(n=4,370,432\):

Wait, why does this look more like a staircase than a slide? Something's going on here.

Heap

There's something nonlinear happening here. We see these discrete runtime spikes occurring at around \(n\approx1\mathrm{e}6\),

\(2\mathrm{e}6\), and \(4\mathrm{e}6\). These threshold-based jumps suggest something about the way BigUint handles large numbers.

Internally, the type is a dynamically sized Vec<usize>; when the number of bits (digits) exceeds a power of 2, the buffer

must reallocate its maximum capacity. This reallocation involves expensive operations like heap allocation and copying old digits.

In essence, the cost per step depends on the current size of BigUint: once

\(\mathrm{F_n}\) reaches a new order of magnitude, each multiplication gets more expensive.

It's worth mentioning the .clone() method used to return our Fibonacci number. BigUint does not implement the Copy trait, so

we can't just move the value out the matrix. For large \(n\), cloning could bottleneck performance, although I couldn't find a way to avoid it.

Fast Doubling

The fast doubling approach makes use of the "double-angle" identities for the Fibonacci numbers. We can arrive at these identities by simply squaring the matrix representation:

$$ \begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{F_{2n+1}} & \mathrm{F_{2n}} \newline \mathrm{F_{2n}} & \mathrm{F_{2n-1}} \end{bmatrix} & = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \newline 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} ^{2n} \newline \newline & = \left( \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \newline 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} ^{n} \right) ^{2} \newline \newline & = \left( \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{F_{n+1}} & \mathrm{F_{n}} \newline \mathrm{F_{n}} & \mathrm{F_{n-1}} \end{bmatrix} \right) ^{2} \newline \newline & = \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{F_{n+1}^{2} + F_{n}^{2}} & \mathrm{F_{n}(F_{n+1} + F_{n-1})} \newline \mathrm{F_{n}(F_{n+1} + F_{n-1})} & \mathrm{F_{n}^{2} + F_{n-1}^{2}} \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned} $$

Note that \(\mathrm{F_{n}(F_{n+1} + F_{n-1})}\) can be written as \(\mathrm{F_{n}(2F_{n+1} - F_{n})}\) using \(\mathrm{F_{n-1} = F_{n+1} - F_{n}}\). Finally, we equate the terms in corresponding matrix entries to get the doubling identities:

$$ \boxed{ \begin{aligned} \mathrm{F_{2n+1}} & = \mathrm{F_{n+1}^{2} + F_{n}^{2}} \newline \mathrm{F_{2n}} & = \mathrm{F_{n}(2F_{n+1} - F_{n})} \end{aligned} } $$

We can use these identities to compute \((\mathrm{F_{n}}, \mathrm{F_{n+1}})\) by recursing on \(\lfloor n/2 \rfloor\), which gives a \(O(\log n)\) recursion depth. Given \((a, b) = (\mathrm{F_{\lfloor n/2 \rfloor}}, \mathrm{F_{\lfloor n/2 \rfloor +1}})\), let

$$ \begin{aligned} c &= a(2b - a) \newline d &= a^2 + b^2 \end{aligned} $$

Our desired Fibonacci numbers are

$$ (\mathrm{F_{n}}, \mathrm{F_{n+1}}) = \begin{cases} (c, d) & \text{if } n \text{ is even} \newline (d, c + d) & \text{if } n \text{ is odd} \end{cases} $$

and we can implement this as follows:

/// Returns (F(n), F(n+1))

fn fib_doubling_recursive(n: usize) -> (BigUint, BigUint) {

match n {

0 => (BigUint::zero(), BigUint::one()),

_ => {

// a := F(n), b := F(n+1)

// We recurse on floor(n/2)

let (a, b) = fib_doubling_recursive(n >> 1);

// c := F(2n) = F(n) * (2*F(n+1) - F(n))

// d := F(2n+1) = F(n)^2 + F(n+1)^2

let t = (&b << 1) - &a;

let c = &a * &t;

let d = &a * &a + &b * &b;

match n & 1 {

0 => (c, d), // Even: F(n) = c, F(n+1) = d

_ => {

// Odd: F(n) = d, F(n+1) = c + d

let sum = &c + &d;

(d, sum)

}

}

}

}

}

/// Entry point

pub fn fib_doubling(n: usize) -> BigUint {

fib_doubling_recursive(n).0

}

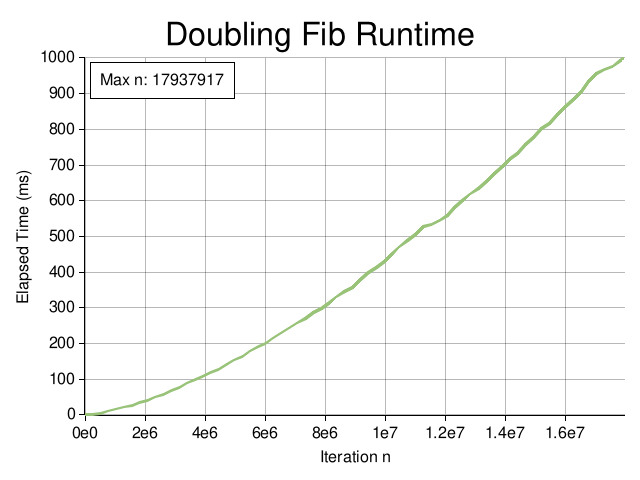

This algorithm is a significant improvement over Matrix Multiplication, achieving a maximum iteration of \(n = 17,937,917\):

The main thing to note is that this process involves just 3 BigUint multiplications: one for calculating \(c\) and two for

\(d\). Compare this to the 8-12 BigUint multiplications required for the Matrix Multiplication method and we can see why Fast Doubling

is able to calculate such large numbers, despite both algorithms being \(O(\log n)\).

Discussion

I tested 4 different methods of calculating Fibonacci numbers in hopes of finding the highest \(\mathrm{F_n}\) in under 1 second. Results largely depended on the algorithm used: the recursive implementation barely calculated the 40th Fibonacci number while the fast doubling method approached almost 18,000,000!

The figures below show a more direct comparison between algorithms:

| Algorithm | Highest n | Time Complexity | Space Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recursive | 38 | O(2n) | O(n) |

| Sliding Win | 694,720 | O(n) | O(n) |

| Matrix Mult | 4,370,432 | O(log n) | O(n) |

| Fast Doubl | 17,937,917 | O(log n) | O(log n) |

I was surprised to find that despite both being \(O(\log n)\) runtime algorithms, matrix multiplication

and fast doubling achieved such drastic iteration differences. I suspect the reason is that fast doubling not only performs fewer BigUint

operations but also takes up less memory. It can therefore benefit more from cache locality and avoid overhead associated with

repeated memory allocations.

This analysis was very preliminary and I'd love to dive deeper into this topic in the future. For example, the BigUint multiplication operations

could be implemented using fast integer multiplication such as Karatsuba or Schönhage–Strassen.

I could also experiment with other Fibonacci/Lucas number identities besides the typical "double-angle" identity.